Next: Eigenstates and Eigenvalues

Up: Fundamentals of Quantum Mechanics

Previous: Momentum Representation

Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle

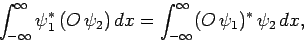

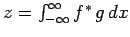

Consider a real-space Hermitian operator  . A straightforward generalization of Eq. (193) yields

. A straightforward generalization of Eq. (193) yields

|

(222) |

where  and

and  are general functions.

are general functions.

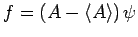

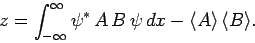

Let

, where

, where  is an Hermitian operator,

and

is an Hermitian operator,

and  a general wavefunction. We have

a general wavefunction. We have

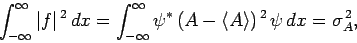

![\begin{displaymath}

\int_{-\infty}^\infty \vert f\vert^{ 2} dx= \int_{-\infty}...

...e A\rangle) \psi]^{ \ast} [(A-\langle A\rangle) \psi] dx.

\end{displaymath}](img607.png) |

(223) |

Making use of Eq. (222), we obtain

|

(224) |

where

is the variance of

is the variance of  [see Eq. (160)].

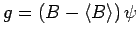

Similarly, if

[see Eq. (160)].

Similarly, if

, where

, where  is a second

Hermitian operator, then

is a second

Hermitian operator, then

|

(225) |

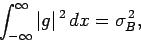

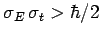

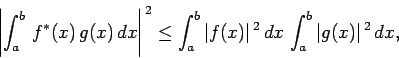

Now, there is a standard result in mathematics, known as the

Schwartz inequality, which states that

|

(226) |

where  and

and  are two general functions. Furthermore, if

are two general functions. Furthermore, if  is

a complex number then

is

a complex number then

![\begin{displaymath}

\vert z\vert^{ 2} = [{\rm Re}(z)]^{ 2} + [{\rm Im}(z)]^{ ...

...]^{ 2} = \left[\frac{1}{2 {\rm i}} (z-z^\ast)\right]^{ 2}.

\end{displaymath}](img614.png) |

(227) |

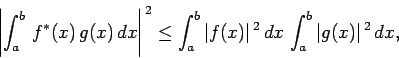

Hence, if

then Eqs. (224)-(227) yield

then Eqs. (224)-(227) yield

![\begin{displaymath}

\sigma_A^{ 2} \sigma_B^{ 2} \geq \left[\frac{1}{2 {\rm i}} (z-z^\ast)\right]^{ 2}.

\end{displaymath}](img616.png) |

(228) |

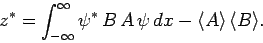

However,

![\begin{displaymath}

z = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} [(A-\langle A\rangle) \psi]^{ ...

...si^\ast (A-\langle A\rangle) (B-\langle B\rangle) \psi dx,

\end{displaymath}](img617.png) |

(229) |

where use has been made of Eq. (222). The above

equation reduces to

|

(230) |

Furthermore, it is easily demonstrated that

|

(231) |

Hence, Eq. (228) gives

![\begin{displaymath}

\sigma_A^{ 2} \sigma_B^{ 2} \geq \left(\frac{1}{2 {\rm i}}\langle[A,B]\rangle\right)^{ 2},

\end{displaymath}](img620.png) |

(232) |

where

![\begin{displaymath}[A,B]\equiv A B-B A.

\end{displaymath}](img621.png) |

(233) |

Equation (232) is the general form of Heisenberg's uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics. It states that if two dynamical

variables are represented by the two Hermitian operators  and

and  ,

and these operators do not commute (i.e.,

,

and these operators do not commute (i.e.,  ),

then it is impossible to simultaneously (exactly) measure the two variables.

Instead, the product of the variances in the measurements is always greater than some critical value, which

depends on the extent to which the two operators do not commute.

),

then it is impossible to simultaneously (exactly) measure the two variables.

Instead, the product of the variances in the measurements is always greater than some critical value, which

depends on the extent to which the two operators do not commute.

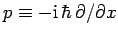

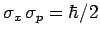

For instance, displacement and momentum are represented (in real-space) by the

operators  and

and

, respectively.

Now, it is easily demonstrated that

, respectively.

Now, it is easily demonstrated that

![\begin{displaymath}[x,p]= {\rm i} \hbar.

\end{displaymath}](img624.png) |

(234) |

Thus,

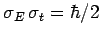

|

(235) |

which can be recognized as the standard displacement-momentum uncertainty

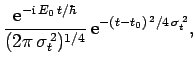

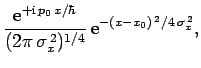

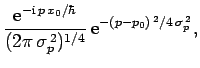

principle (see Sect. 3.14). It turns out that the minimum uncertainty (i.e.,

) is only achieved by Gaussian wave packets (see Sect. 3.12): i.e.,

) is only achieved by Gaussian wave packets (see Sect. 3.12): i.e.,

where  is the momentum-space equivalent of

is the momentum-space equivalent of  .

.

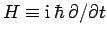

Energy and time are represented by the operators

and

and  , respectively. These operators do not commute,

indicating that energy and time cannot be measured simultaneously.

In fact,

, respectively. These operators do not commute,

indicating that energy and time cannot be measured simultaneously.

In fact,

![\begin{displaymath}[H,t]= {\rm i} \hbar,

\end{displaymath}](img633.png) |

(238) |

so

|

(239) |

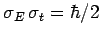

This can be written, somewhat less exactly, as

|

(240) |

where  and

and

are the uncertainties in

energy and time, respectively. The above expression is generally

known as the energy-time uncertainty principle.

are the uncertainties in

energy and time, respectively. The above expression is generally

known as the energy-time uncertainty principle.

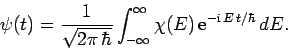

For instance, suppose that a particle passes some fixed point on the  -axis.

Since the particle is, in reality, an extended wave packet, it takes a certain amount

of time

-axis.

Since the particle is, in reality, an extended wave packet, it takes a certain amount

of time  for the particle to pass. Thus, there is an uncertainty,

for the particle to pass. Thus, there is an uncertainty,

, in the arrival time of the particle. Moreover, since

, in the arrival time of the particle. Moreover, since

, the only wavefunctions which have unique energies

are those with unique frequencies: i.e., plane waves. Since a

wave packet of finite extent is made up of a combination of plane waves

of different wavenumbers, and, hence, different frequencies, there will

be an uncertainty

, the only wavefunctions which have unique energies

are those with unique frequencies: i.e., plane waves. Since a

wave packet of finite extent is made up of a combination of plane waves

of different wavenumbers, and, hence, different frequencies, there will

be an uncertainty  in the particle's energy which is

proportional to the range of frequencies of the plane waves making up the

wave packet. The more compact the wave packet (and, hence, the

smaller

in the particle's energy which is

proportional to the range of frequencies of the plane waves making up the

wave packet. The more compact the wave packet (and, hence, the

smaller  ), the larger the range of frequencies of the constituent plane waves (and, hence, the large

), the larger the range of frequencies of the constituent plane waves (and, hence, the large  ), and

vice versa. To be more exact, if

), and

vice versa. To be more exact, if  is the wavefunction

measured at the fixed point as a function of time, then we can write

is the wavefunction

measured at the fixed point as a function of time, then we can write

|

(241) |

In other words, we can express  as a linear combination of

plane waves of definite energy

as a linear combination of

plane waves of definite energy  . Here,

. Here,  is the complex

amplitude of plane waves of energy

is the complex

amplitude of plane waves of energy  in this combination. By Fourier's

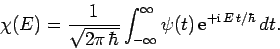

theorem, we also have

in this combination. By Fourier's

theorem, we also have

|

(242) |

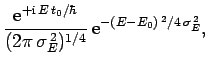

For instance, if  is a Gaussian then it is easily shown that

is a Gaussian then it is easily shown that

is also a Gaussian: i.e.,

is also a Gaussian: i.e.,

where

. As before, Gaussian wave packets

satisfy the minimum uncertainty principle

. As before, Gaussian wave packets

satisfy the minimum uncertainty principle

. Conversely, non-Gaussian wave packets

are characterized by

. Conversely, non-Gaussian wave packets

are characterized by

.

.

Next: Eigenstates and Eigenvalues

Up: Fundamentals of Quantum Mechanics

Previous: Momentum Representation

Richard Fitzpatrick

2010-07-20

![]() , where

, where ![]() is an Hermitian operator,

and

is an Hermitian operator,

and ![]() a general wavefunction. We have

a general wavefunction. We have

![]() and

and ![]() ,

and these operators do not commute (i.e.,

,

and these operators do not commute (i.e., ![]() ),

then it is impossible to simultaneously (exactly) measure the two variables.

Instead, the product of the variances in the measurements is always greater than some critical value, which

depends on the extent to which the two operators do not commute.

),

then it is impossible to simultaneously (exactly) measure the two variables.

Instead, the product of the variances in the measurements is always greater than some critical value, which

depends on the extent to which the two operators do not commute.

![]() and

and

![]() , respectively.

Now, it is easily demonstrated that

, respectively.

Now, it is easily demonstrated that

![]() and

and ![]() , respectively. These operators do not commute,

indicating that energy and time cannot be measured simultaneously.

In fact,

, respectively. These operators do not commute,

indicating that energy and time cannot be measured simultaneously.

In fact,

![]() -axis.

Since the particle is, in reality, an extended wave packet, it takes a certain amount

of time

-axis.

Since the particle is, in reality, an extended wave packet, it takes a certain amount

of time ![]() for the particle to pass. Thus, there is an uncertainty,

for the particle to pass. Thus, there is an uncertainty,

![]() , in the arrival time of the particle. Moreover, since

, in the arrival time of the particle. Moreover, since

![]() , the only wavefunctions which have unique energies

are those with unique frequencies: i.e., plane waves. Since a

wave packet of finite extent is made up of a combination of plane waves

of different wavenumbers, and, hence, different frequencies, there will

be an uncertainty

, the only wavefunctions which have unique energies

are those with unique frequencies: i.e., plane waves. Since a

wave packet of finite extent is made up of a combination of plane waves

of different wavenumbers, and, hence, different frequencies, there will

be an uncertainty ![]() in the particle's energy which is

proportional to the range of frequencies of the plane waves making up the

wave packet. The more compact the wave packet (and, hence, the

smaller

in the particle's energy which is

proportional to the range of frequencies of the plane waves making up the

wave packet. The more compact the wave packet (and, hence, the

smaller ![]() ), the larger the range of frequencies of the constituent plane waves (and, hence, the large

), the larger the range of frequencies of the constituent plane waves (and, hence, the large ![]() ), and

vice versa. To be more exact, if

), and

vice versa. To be more exact, if ![]() is the wavefunction

measured at the fixed point as a function of time, then we can write

is the wavefunction

measured at the fixed point as a function of time, then we can write